Last year, 52 per cent of the British people voted to leave the EU, a landmark event branded as “Brexit.” Since then, there has been a lot of uncertainty about how Brexit could affect the UK economy, especially the banking sector.

In this article, I explore the expected effects of Brexit on the UK financial market, evaluate their merits and probability, and speculate on the long-term implications on the global financial sector.

By all accounts, the immediate outcome of the Brexit referendum was bleak: stock markets plummeted, sterling lost, and consumer confidence plummeted.

The banking market has been one of the most talked-about industries for a variety of reasons.

The first reason is that the banking industry is a hugely dominant field in the British economy, accounting for 12 per cent of the overall GDP.

Regardless of output figures, it employs over two million people and is the country’s largest export market, responsible for almost half of the UK’s $31 billion trade surplus in services.

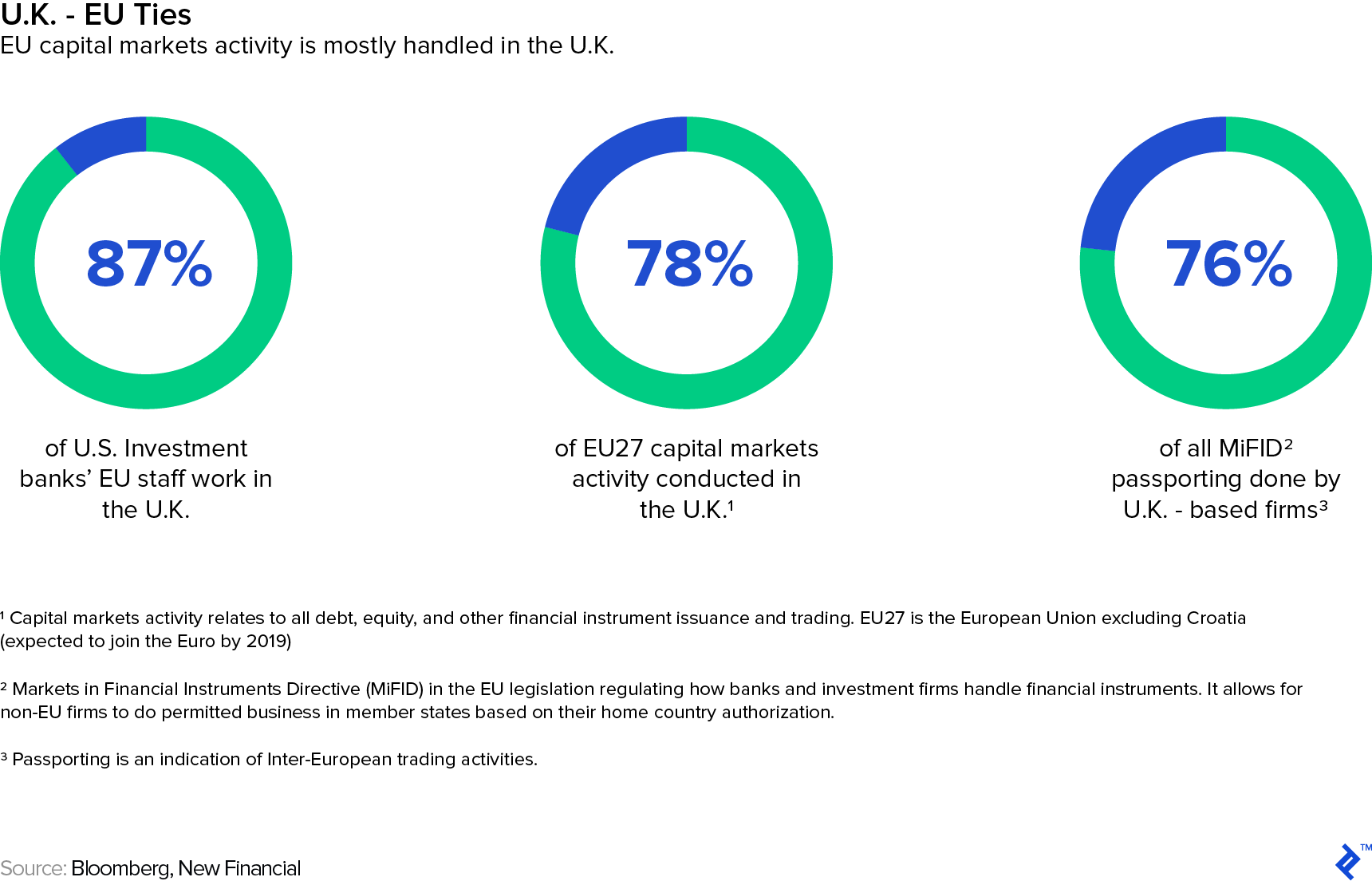

The importance of the UK banking sector to the rest of the EU is also obvious. Nearly $1.4 trillion is lent by British banks to EU businesses and governments. Most of Europe’s financial activity is conducted either directly or indirectly by London (87 per cent of US investment banks’ EU employees work in London).

Since then, stocks have stabilized, putting an end to fears about the British economy’s impending ruin. Nonetheless, there are serious concerns about the long-term effects of Brexit on the UK economy.

The financial sector has been one of the primary beneficiaries of the single market, which is 2nd reason. Economic motivations are deeply ingrained in the EU.

With all of this in mind, it’s no surprise that financial services have received the brunt of the post-Brexit doom and gloom.

Is Brexit a Big Deal?

Unfortunately, yes appears to be the most possible response.

An analysis of the banking sector’s problems and worries yields a slew of alarming conclusions.

These revolve around three major issues: passporting, regulatory instability, and talent emigration.

1. Passporting: what is it and why is it Important?

The passporting issue is by far the most relevant issue at hand.

Passporting is the mechanism by which any British-based financial company, such as banks, insurance companies, and wealth management firms, may market their goods and services in the EU without the need for a licence, regulatory permission, or the establishment of local branches.

Passporting, along with a few other core factors discussed below, has been a major factor in the decision of a large number of financial institutions to establish headquarters in London.

According to a new survey, almost 5,500 UK businesses use passporting to do business with the rest of the EU. And the flows are reciprocal. Using passporting laws, over 8,000 companies from the rest of the EU trade into the UK.

Would passporting proceed as Brexit approaches? The response seems to be a resounding no.

The best way for Britain to keep its passporting benefits will be if it pursued a “Norwegian deal” with the EU (membership of the European Economic Area and adherence to all its associated rules).

A Norwegian-style approach, on the other hand, is highly impossible since it would compel Britain to negotiate on the same issues (specifically, immigration) that prompted the Brexit referendum in the first place.

Is there any other way for UK companies to export into the EU without passporting? One option will be to pursue a “Swiss deal” with the EU (essentially one focused on bilateral trade agreements).

However, a Swiss-style approach seems unlikely.

“It is doubtful that the UK will get a deal with the EU as nice as Switzerland’s”. The Swiss made their agreement while they were preparing to enter the EU; a nation leaving the EU would generate less goodwill.”

And even if it were achieved, there are strong doubts about the efficacy of such a model. More specifically, the “Swiss model” takes advantage of the so-called “third country equivalence” rules, which allow for non-member state firms to perform some of the same functions that passporting allows for.

If both a Norwegian model and a Swiss model seem difficult, is there a third option?

The response is yes, and that will mean a single Free Trade Agreement, close to what Canada and South Korea have signed with the EU.

However, these negotiations are lengthy and complex (for example, the Canada-EU negotiations have taken seven years) and will, in any event, result in far more restrictive terms than the existing passport rights allow.

2. Regulatory Uncertainty is on the Horizon

Regulatory uncertainty is the second key topic to be addressed in the context of Brexit.

To be sure, regulation has traditionally been one of Britain’s strengths, at least in judging why London has become Europe’s (and perhaps the world’s) financial capital. For two reasons:

- English law provides some real benefits regarding topics like debt issuance and insolvency law.

- British labour rules are much more relaxed and employer-friendly than their counterparts in continental Europe. (e.g. a recent report in the Financial Times cites a jobs lawyer as saying that a senior banker making $1.5 million in gross compensation could normally be made obsolete for a $150,000 bonus in London, but the expense could currently be 10 to 15 times that in Frankfurt’)

But, although this may have been a strength in history, Brexit complicates matters considerably.

First, Britain would need to replicate or renegotiate more than 40 years of EU rules and trade agreements. Obviously, this would take a considerable amount of time. Unfortunately, many financial services companies cannot afford to delay that long.

Second, aside from timing issues, it is not even clear whether new UK financial regulations would be good for the sector.

To be honest, this was, in reality, one of the reasons that the Brexit-proponents called for in favour of leaving the Union. Freed from the grip of excessive Brussels bureaucracy, concluded that Britain might enter a new age of deregulation that would really improve the financial sector.

Overall, while an independent regulatory environment could indeed be a long-term benefit, the short-term impact of regulatory uncertainty may prove too much to be dealt with by many of London’s firms.

3. The Danger of Brain Draining

The third key reason why it could cause long-lasting damage to the British Banking sector is that Brexit could set off a dangerous brain drain that would undermine one of the main reasons for London’s rise to prominence.

London, like Silicon Valley, enjoys a critical mass of world-class, industry-specific talent living and working in close proximity. In a recent interview with the Wall Street Journal, UBS CEO made that clear: “[There are] three major reasons why we are in London. First and foremost, the reservoir of talent.”

But does this continue to be the case in the post-Brexit world? Disruptions, such as visa insecurity for foreign workers and near-term job-loss opportunities, may force top talent to move elsewhere.

Specifically, on the subject of visas, a new study found that ‘if the existing visa scheme were applied to EU migrants, evidence indicates that three-quarters of the EU labour force in the UK will not fulfil these conditions.’ This will be a big problem for the City of London, where 12% of the population is European (and much of it in the banking sector).

Once the wheels are set on a talent-exodus, it can be impossible to change the cycle.

Network effects are strong and work both ways-to draw talent as well as to turn it out.

The crux of it all is that talent is mobile, and while London already has the best collection of factors to draw top talent, there are many other decent-looking alternatives ready to bite at its heels should Brexit start taking its toll.

How Banks are preparing for Brexit?

Individual banks must not just look at the high-level effect of Brexit in all its ways, but must also take initial measures to develop contingency planning and minimise identified problems. Banks are currently reacting in the following manner:

Worst case preparation: given the level of uncertainty and the considerably greater implications of the hard Brexit, the majority of banks are planning to do so as a worst-case scenario and are exploring operating model designs that would enable them to continue to have European client coverage in an area where UK companies do not have access to the European market. With the European Banking Authority (EBA) issuing guidelines that signal that it would not allow the creation of empty shells within the EU to have such access, companies are exploring options to expand existing institutions or establish new ones within the EU with sufficient management, governance, personnel and resources to monitor the risks they produce. This gets more complicated in view of the uncertainty that still exists as regards the existence of the prohibitions on cross-border transfers between the United Kingdom and the EU and the regulations on access to EU-approved central counterparties (CCPs).

Delaying: In many situations, the degree of confusion surrounding the results of the Brexit causes the banks to postpone the full start of the implementation activities. While a high degree of impact analysis may have been carried out and a high-level operating model established, many of the more detailed aspects of execution, where specifications are not transparent, are delayed until more is understood. The European Council meeting of 22 and 23 March 2018 offered some guidelines on possible transitional and final-state plans, but much negotiation remains to decide the final agreement.

Final Thoughts

The impact on banks and banking in the UK will be partially dictated by negotiations between policymakers and regulators on several pieces of legislation and how companies react to this changing environment. The extent to which connectivity to the EU is maintained can vary significantly.